By CRISTINA JANNEY

Hays Post

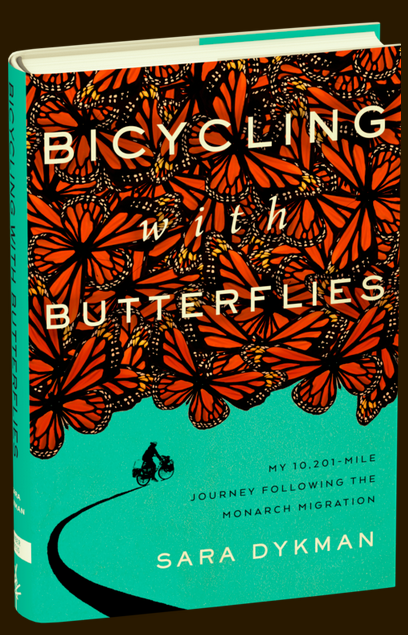

Sara Dykman bicycled more than 10,000 miles following both the spring and fall migrations of the monarch butterfly in 2017.

She chronicles her story in her book "Bicycling with Butterflies." Dykman, who is from Kansas City, made her first in-person book tour appearance at the Hays Public Library on Sept. 8.

Dykman said if her audience only learned one thing from the presentation she wanted them to know that monarch butterfly caterpillars eat milkweed, a flower with 90 native species in the U.S, Mexico and Canada.

"The monarch is 100 percent connected to this plant this male butterfly is nectaring on, which is milkweed. No milkweed, no monarchs," she said.

Milkweed is the only plant that monarch caterpillars will eat. It makes them poisonous and helps to protect them from predators.

"It's not only good [for monarchs]," she said of the milkweed, "it is the only way we are going to save them."

The latest estimates are monarchs need 1 billion stems of milkweed to maintain their migration.

The adult butterflies also need flowers from which they drink nectar.

Dykman started her journey in March in Mexico as the monarchs were leaving their overwintering site in the Oyamel fir forests of Mexico.

She said this was the most butterflies she would see until the butterflies started to regroup for their migration back south. Most of her journey, she would only see a few per day.

Monarchs are the only butterfly known to make a two-way annual migration. The butterflies migrate from southern Canada to Mexico each fall. They overwinter in Michoacán, Mexico, and then begin their journey north in the spring.

As they encounter milkweed, females lay their eggs and then die. The butterflies continue to reproduce and die as they move north. Several generations later, butterflies that were never in Mexico make the migration south in the fall to the overwintering site.

"That never gets old to me," Dykman said. "To look at a little egg next to a railroad track in Illinois and be like 'You are going to metamorphose and you are going to fly to a tree that your great-great-great grandma was on."

Most of the monarchs that migrate to Mexico come from east of the Rocky Mountains. Most of the monarchs west of the Rockies overwinter in southern California. A few of the eastern monarchs overwinter in Florida.

The migratory monarch butterflies recently made the International Union for Conservation of Nature endangered list. Although monarch butterflies can be found worldwide, their migration in North America is under threat due to habitat destruction, use of pesticides and herbicides, and climate change.

The IUCN list is not the U.S. federal endangered species list that would give the butterflies and their habitat more protection in the United States.

"This migration is what's at stake," Dykman said. "This multi-generational, multi-national migration is what we're fighting to save."

Dykman gave presentations to schools and community groups on her journey. With the exception of her presentation stops, she said she "threw everything I needed on that bike, and I just didn't have a plan."

"When I was hungry, I would stop and cook," she said. "When I was tired, I would stop and camp."

She said camping in unestablished camp spots, was very cheap and she was separate from people who might be a threat.

"I felt really, really safe," she said.

She said bike touring makes her grateful for the smallest things.

"I always say my most two favorite things are an outlet, close to lunch time, even more than a shower, and a tree to lean your bike up against at night," she said.

She said it also gave her a better understanding of monarch habitat.

"If it's safe during the first mile and the last mile, that doesn't matter if it's not safe the middle mile," she said. "It's the same with the monarchs. They can have all the habitat they need in Mexico. They can have all the habitat they need in Canada, but if they don't have habitat in Kansas, the whole trip doesn't matter."

Dykman said designating wild lands as national and state parks and wildlife refuges will not help monarchs unless there are milkweed and nectar-producing flowers all along their migration route.

"There's a movement going on right now to get these native gardens at every single person's house and every single planter box and every single church and every single library. Any place there's green grass, if we can get native plants there, we're offering a caterpillar a home."

Now is the time to plant milkweed seeds, as they need to go through a process of cold and wet to germinate in the spring.

Dykman said she stopped often to view and take photographs of monarchs and other insects and animals during her trip. She would look for caterpillar poop or the distinctive horseshow-shaped holes in milkweed leaves that indicated a young monarch caterpillar had been eating a milkweed leaf.

"This is what my trip was about. It was seeing the world through the lens of a monarch," she said.

However, she said she saw habitat destruction that she didn't want to see.

Mowing roadside ditches, especially in the fall during the monarch migration, not only destroys monarch food, but it is likely to kill monarch caterpillars that are feeding on milkweed in those ditches, Dykman said.

Dykman urged local residents to contact their municipalities to urge officials not to mow, leave areas native or at least delay mowing until after the migration.

"I think that is one of the most important lessons that the monarchs taught me is that you're going to be depressed unless you go out and try to do something and try to fix it," she said.

"You can't just complain without a solution. My solution was to be their voice."

Species like frogs are very particular about their habitat.

"Monarchs don't mind if there's 99 percent pavement here, I'll put an egg on this milkweed in this planter box," she said.

Dykman urged her audience that even if monarchs are not your thing, pick something else in the environment to champion.

"If your protecting frogs, you're protecting monarch. If you're protecting monarchs, you're protecting frogs. It's all connected," she said. "It doesn't matter what calls you. Find something that does and go take care of that thing."

You can learn more about Dykman's work on butterfly conservation on her website Beyond A Book. There is also a link on that site to order her book.

Other resources on monarch butterflies

Monarch Watch

Monarch Joint Venture